The Case For Chaos

W+K Amsterdam's Martin Weigel breaks down the difference between what the corporation wants and what creativity needs.

+AMS

Recently, W+K Amsterdam head of planning Martin Weigel was invited to speak at the Agency Leaders Symposium in Hunter Valley, where he revisited at theme he's written about at length: chaos and creativity. We've reproduced his talk here.

The result?

What the corporation wants and what creativity needs are different. We will make no progress until we understand this, and navigate the tension with intelligence.

So let’s consider briefly the corporate instinct.

The corporation has always been an exercise in control, process, and replicability. And indeed much of the corporation–from supply chain management to human resources to legal to logistics to manufacturing to finance to legal–can be subjected to repeatable rules, formulas, and standardised practices. And, in the fullness of time given over to algorithms, A.I., and robots.

The instinct for order and control is understandable.

As Schumacher put it in his 1973 classic, Small Is Beautiful:

"Without order, planning, predictability, central control, accountancy, instructions to the underlings, obedience, discipline–without these nothing fruitful can happen, because everything disintegrates."

But.

For when we succumb to the fantasy that we can professionalise creativity, that we can extract the play, unpredictability, and human element out of the process, that it can be treated like the manufacturing process, repeatable and reliable in its methods, then we place the potential of creativity in serious jeopardy.

That’s fine if you’re running a manufacturing plant, but not if you’re in the market for creativity.

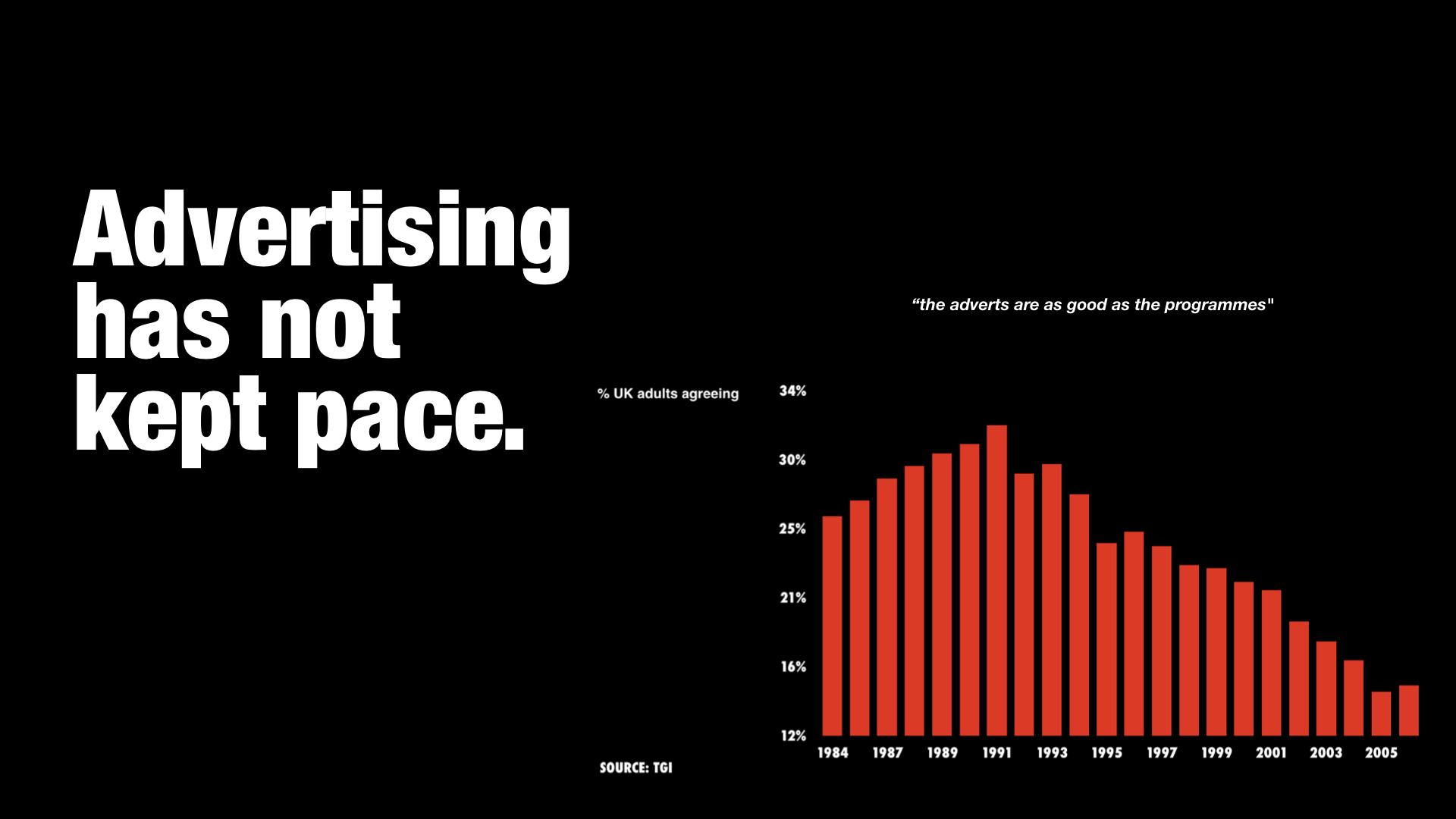

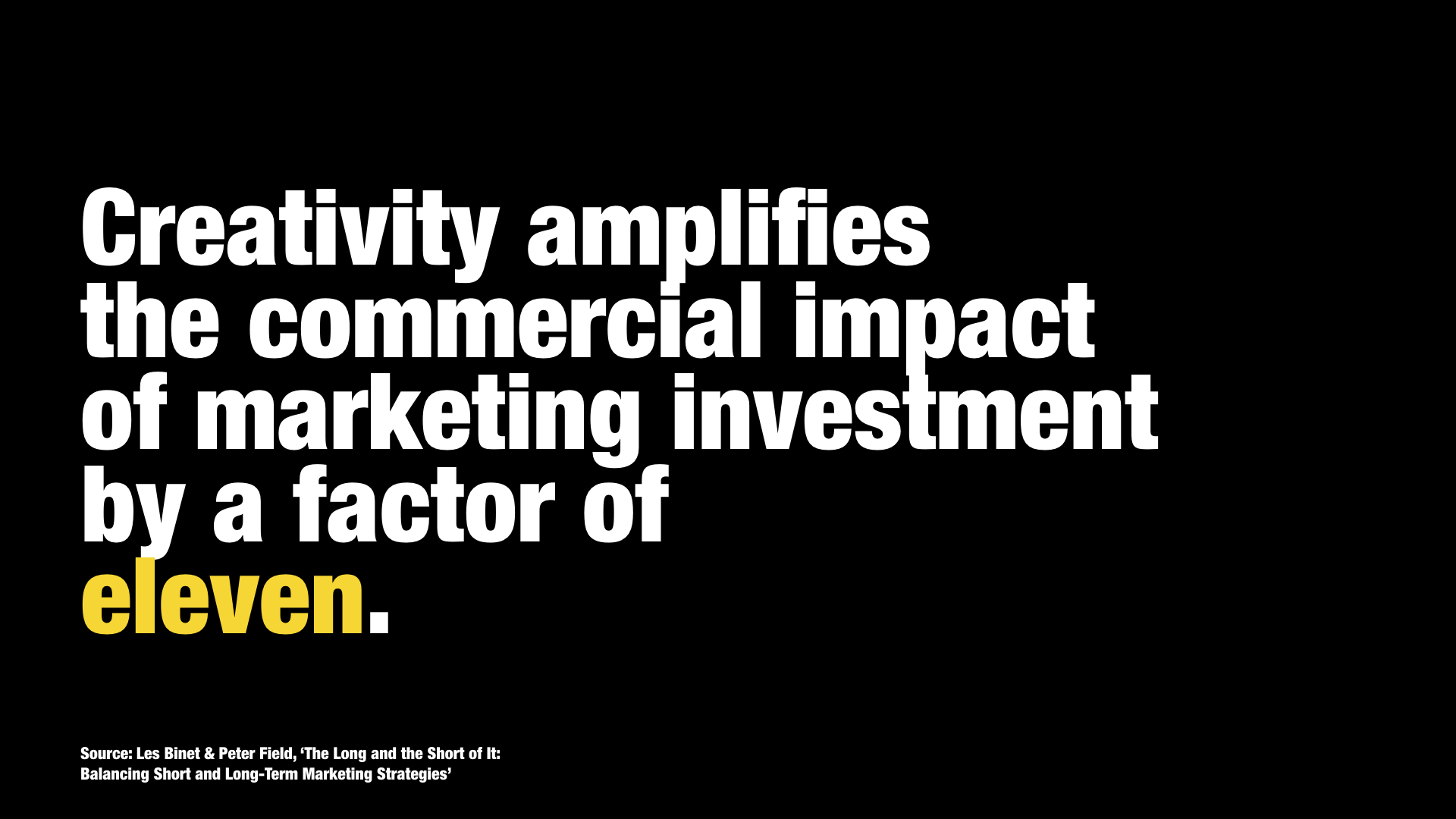

And we know the value of creativity.

It’s eleven.

We know from the work of Binet and Field published by the IPA in its report The Link Between Creativity And Effectiveness, that creativity amplifies the impact of marketing monies (measured as share growth) by a factor of 11.

But the creativity–the stuff that captures the imaginations of people and enters arteries of culture and that creates this value cannot be born out of orderly, logical, linear IF THIS THEN THAT processes and systems.

Now it is worth noting at this point that some advertising tasks—particularly those at the bottom end of the funnel where we’re converting interest into action–can be reduced to If This Then That systems.

But what works for converting existing interest or intent into purchase does not automatically translate into what works for exciting the indifferent, creating that interest (or indeed, for sustaining pricing–the oft-overlooked turbocharger of profit creation)–a distinction that we ignore or misunderstand at our peril.

Now this tension between what the corporation wants and what creativity needs doesn’t have to freak us out. It’s not new. It’s not unusual. It’s not an aberration. The tension is a feature, not a bug.

Nonetheless, creativity must strive to become undomesticated.

So some suggestions for how to create the space, conditions, and environment in which creativity can realise its promise and potential:

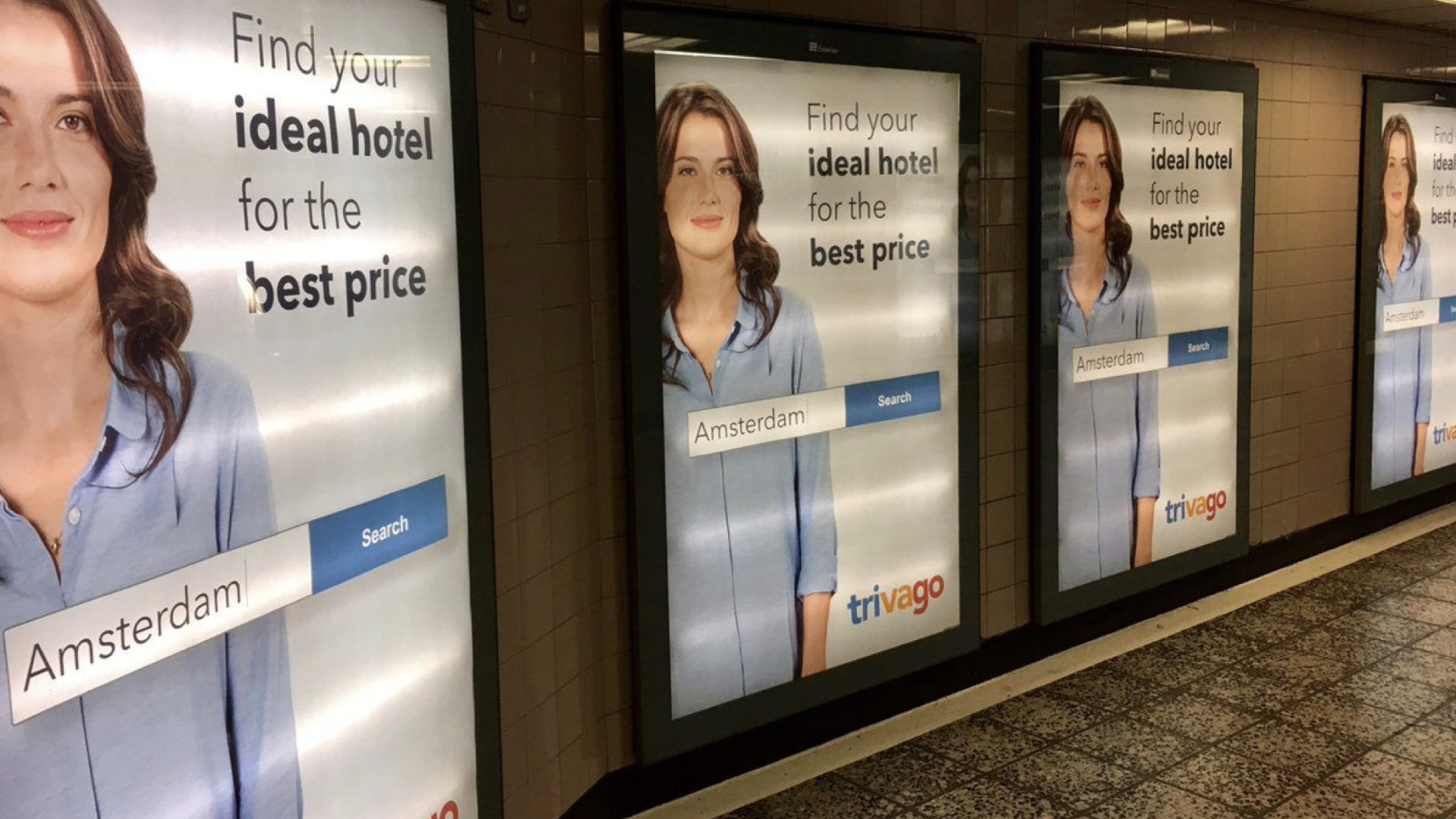

Locked in meetings or glued to screens too many marketers have too little meaningful contact with real people in the real world.

A entirely theoretical construct encountered only in research reports.

When we only see "consumers" or "impressions," or "traffic," or "clicks," we dehumanize the whole enterprise, and reduce people to just another component into a piece of machinery we call marketing. And in so doing, we reduce marketing to Newtonian physics where bodies (formerly known as human beings) are acted on by forces (or messages), and sales, revenue, profit or whatever is emitted.

The few moments of what passes for real world contact these days are reduced to putting people in a sterile windowless environment, telling them they’re being watched by anonymous observers, subjecting them more often than not to stupid questions and calling it "learning."

It isn’t real life.

It’s people ripped out of the contexts of their daily lives, their homes, their families, their jobs. At best it provides us with a distorted version of reality.

And lest anybody believe it’s the cure-all solution, while its powers, benefits, and applications are legion, more data is not the solution.

The truth is that marketing done well, or effectively, demands contact.

You can’t claim to want to shape culture if you never make contact with it.

We are surrounded by this stuff.

Orthodoxies, models, best practises and universal theories might make life more simple and obviate the need for independent thinking and lighten the marketer’s cognitive load. We can follow the rules, accept the wisdom, tick the boxes or throw everything into a black box testing process and let it tell us what to do.

They make us slaves to other people’s creative ideologies, prejudices, wild theories, zombie ideas, and assumptions.

And they blind and limit us to the infinite ways in which creativity can work.

As Paul Feldwick puts it in his survey of advertising history and thought, The Anatomy of Humbug:

"There is much more possible diversity in ways of thinking about advertising than we normally allow… we could use this diversity to give us greater scope ion what we do. For all its talk of 'creativity' and 'thinking outside the box,' the ad business today is in danger of losing its diversity. Creative people and marketing people alike each go to the same schools, learn the same things, and the same things they learn are too often a third-hand mash-up of Reeve’s USP theory and Bernbach’s vague creative rhetoric. But in creating ads, we still have the full resources of human culture at our disposal. Ads don’t need to look like they were written by Bernbach 60 years ago, or like last year’s Cannes winner."

So whatever research vendors and inherited wisdom might tell us, there is no one way in which communication works. And any research provider offering a one-size-fits-all methodology or model is kidding themselves–and you–if they think they’re open-minded.

Liberating creativity demands organizations make themselves safe places for dissent.

Organizations will always provide reward for conformity. As Cass Sunstein, Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Chicago, has written:

"In the real word, people will silence themselves for many reasons. Sometimes they do not want to risk the irritation or opprobrium of their friends and allies. Sometimes they fear that they will, through their dissent, weaken the effectiveness and reputation of the group to which they belong. Sometimes they trust fellow group members to be right."

The rewards of dissent are far less certain, but they can have enormous value.

When it comes to group decision-making for example, studies have demonstrated how the existence of even just one dissenting voice can dramatically reduce both conformity and error and that without the existence and voicing of dissent, we lay ourselves open to potentially limiting and sometimes downright dangerous phenomena.

Without the voice of dissent we will very often use the decisions and actions of other people around us as the best source of information and guidance on what to do.

Similarly, without the voice of dissent, so-called "social cascades" can occur, in which social groups blindly pick up and mimic the behaviours of other groups without actually examining the information they themselves hold.

And without the voice of dissent group polarization can occur. In this phenomenon, our tendency towards conformity means that when it comes to collective decision making processes, group members end up exaggerating their in-going tendencies and taking an even more extreme position.

Yet studies have shown that how even just one dissenting voice can dramatically reduce both conformity and error.

Just imagine…

Marketing long ago put insight and relevance on a pedestal.

And linear, logical process can get you to relevance–"people want This so give them That."

But relevance alone just isn’t enough.

Relevance today is no longer enough because we compete in an over-saturated, hyper-charged cultural marketplace in which every citizen now has access to the creative tools and networks of distribution. They’re all vying for people’s time and attention–unrestrained most of the time by good taste, legal departments, policy teams, PR minders or the brakes of copy-testing.

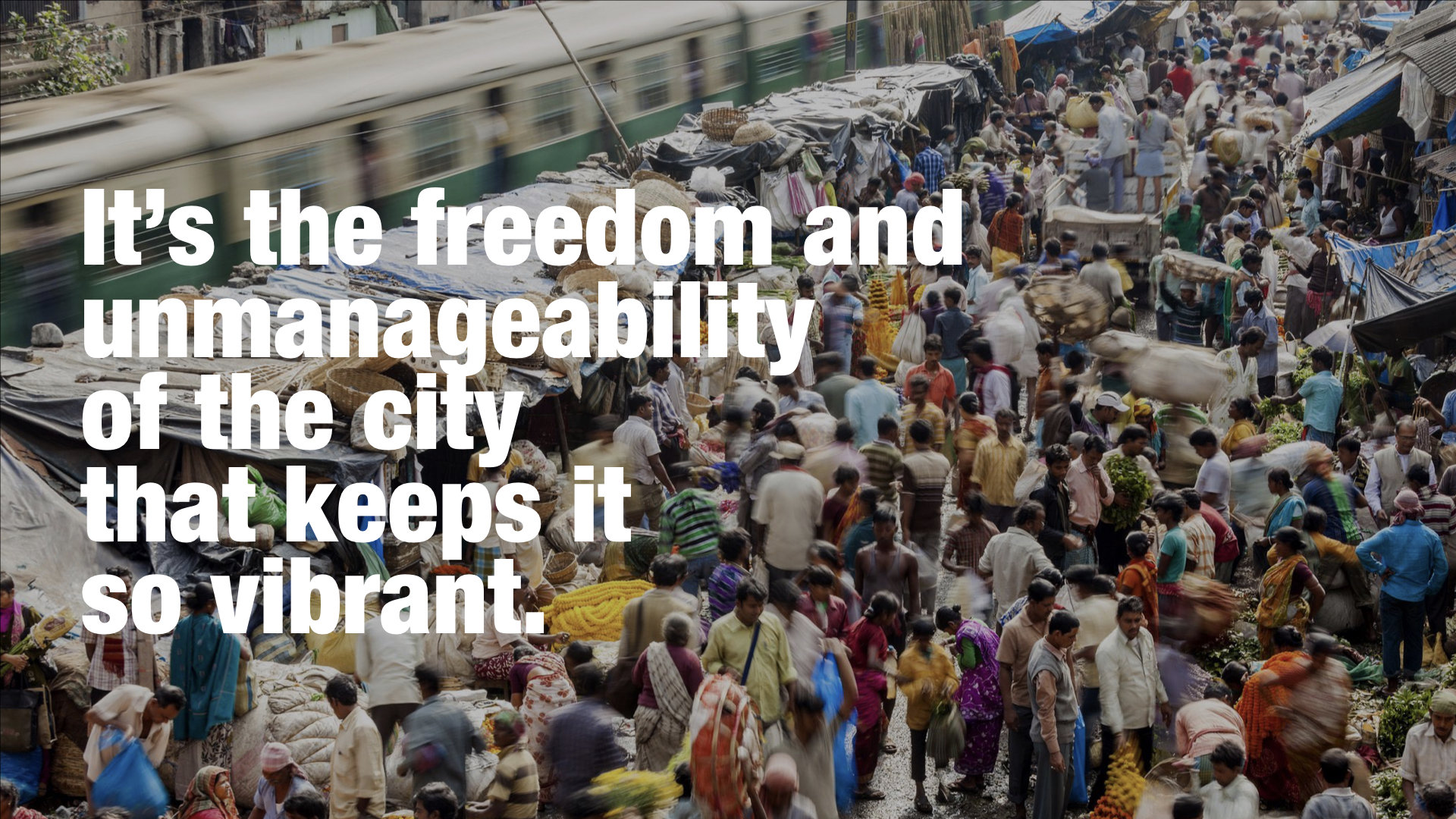

We need organizations capable of learning and adaptation–where ideas are allowed to roam free, flow, and interact, That being the very essence of creativity. And here we have much to learn from how cities function and prosper.

The theoretical physicist Professor Geoffrey West of the Santa Fe Institute is interested in the subject of vigor and has been turning his attention from scaling effects in the natural world to the causes of corporate mortality and the dynamism of cities. And his analysis of how cities and corporations operate is instructive.

Cities are creative, productive, innovative, and wealthy because of their incredible diversity and multi-dimensionality.

And what of the corporation? Well as the social scientist John Gardner notes…

In contrast to cities, as they grow companies allow themselves to be dominated by bureaucracy and administration over creativity and innovation, strangling variance and diversity–signing in effect, their own death warrant.

The solution quite obviously lies not in more or different mechanisms of control, but in resisting their stranglehold on both minds and ways of working.

The protection and nurturing of culture is creativity’s best hope.

For culture operates through shared values, shared ambitions, focuses on outputs not inputs and processes, and provides the space for individual initiative.

So for the corporation wishing to stay agile enough to survive in a world of flux and uncertainty, culture is or should be everything.

It seeks to replace the subjective, individual human element with common, standardized practices.

This is fine if you are a food producer, doctor, or accountant.

But…

The creative process and the shape of its outputs are evolving and diversifying.

This for example, is Wieden in 2009, shooting our "Write The Future" commercial for Nike with an A-list Hollywood director and a crew to match:

This is Wieden in 2017. Here’s the creative team shooting 33 films for Instagram. On an iPhone. With the app. Themselves:

Clearly how we work and what we make is expanding and diversifying.

We must all make the most of this magnificent opportunity.

If the marketing organization is to stay flexible, fluid, willing to try new things once, if it’s to remain vigorous, and adaptable, if it’s not to become buried under the weight of best practice, benchmarks, process and inherited "wisdom," then it’s going to need reclaim its empathy, cast certainty to one side, stop pretending we can professionalise what resists codification, and stop taking it (and ourselves) so seriously.

Or as Professor West puts it, "Allow a little bit more room for bullshit."

Martin Weigel is head of planning at Wieden+Kennedy Amsterdam. Read more from him here.

Share on